MAUREEN MULLARKEY

Artist Statement

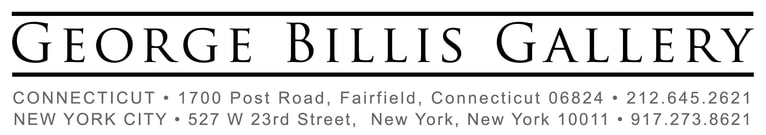

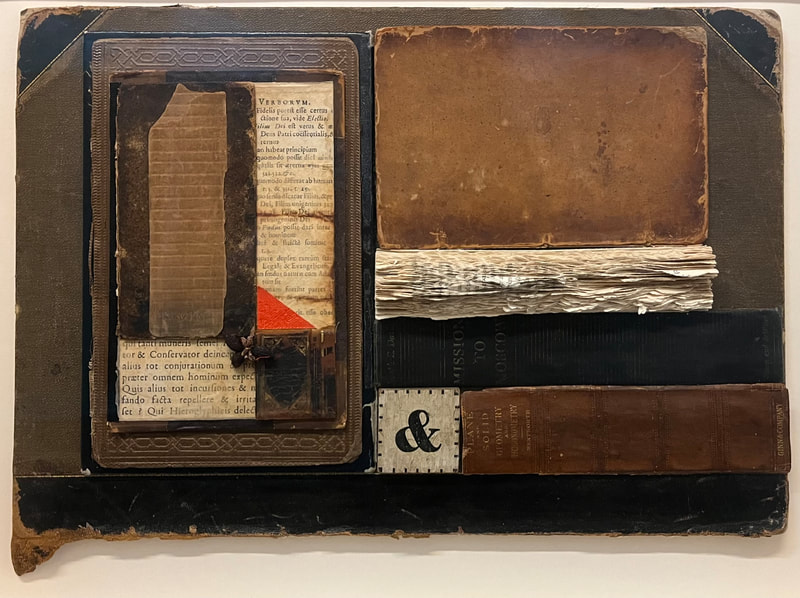

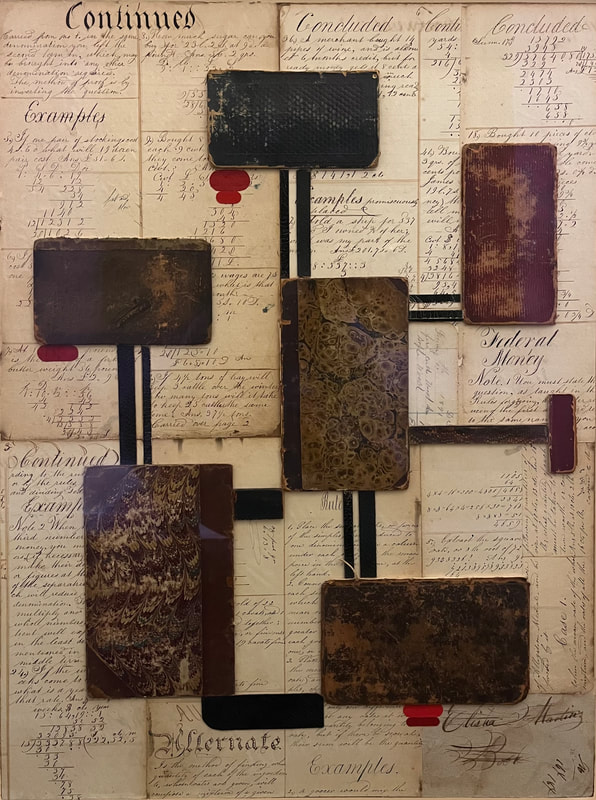

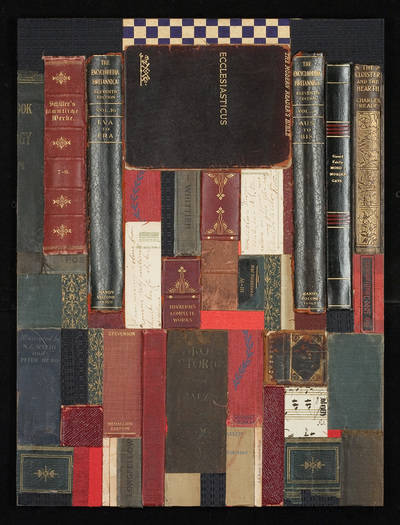

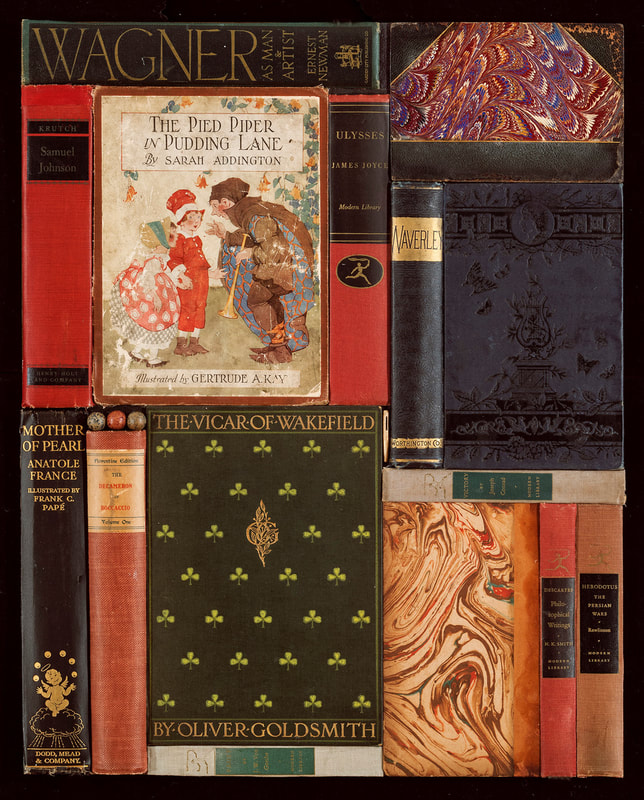

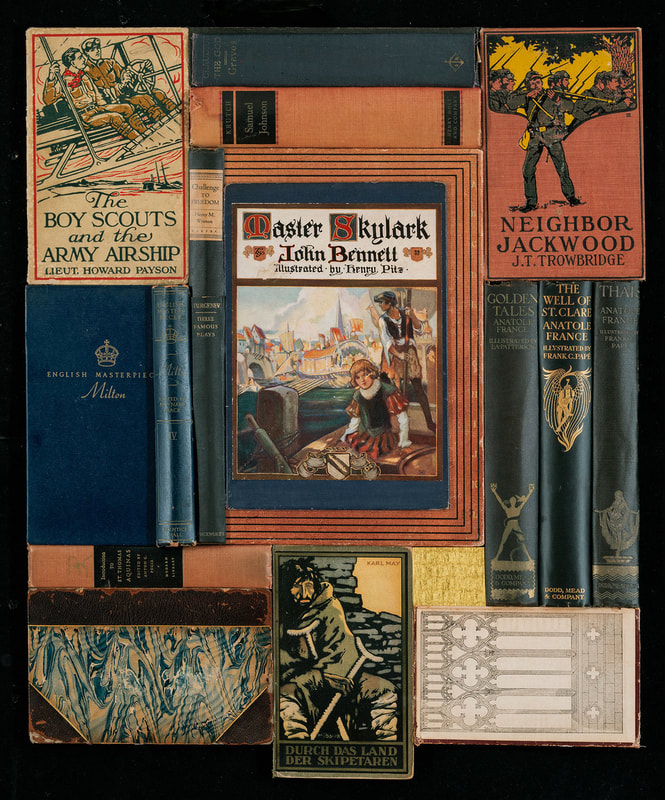

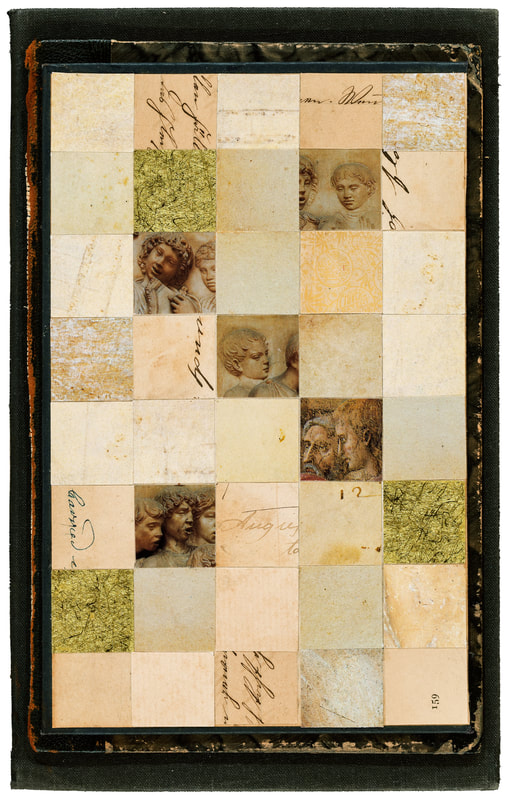

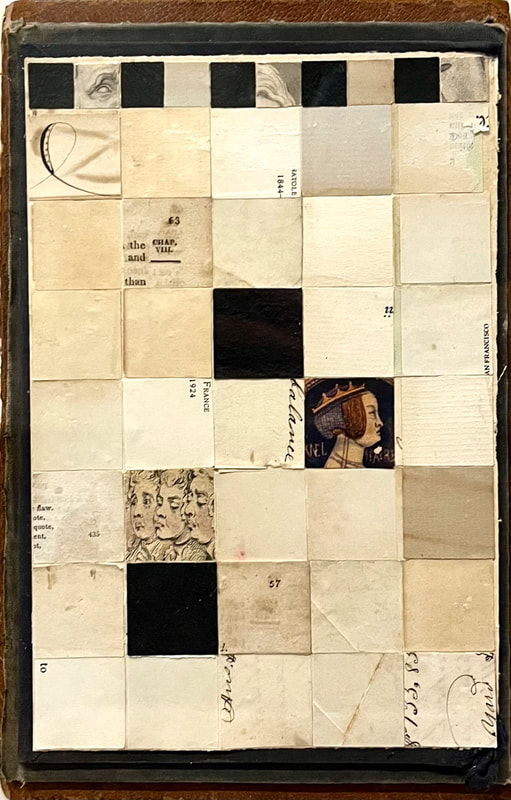

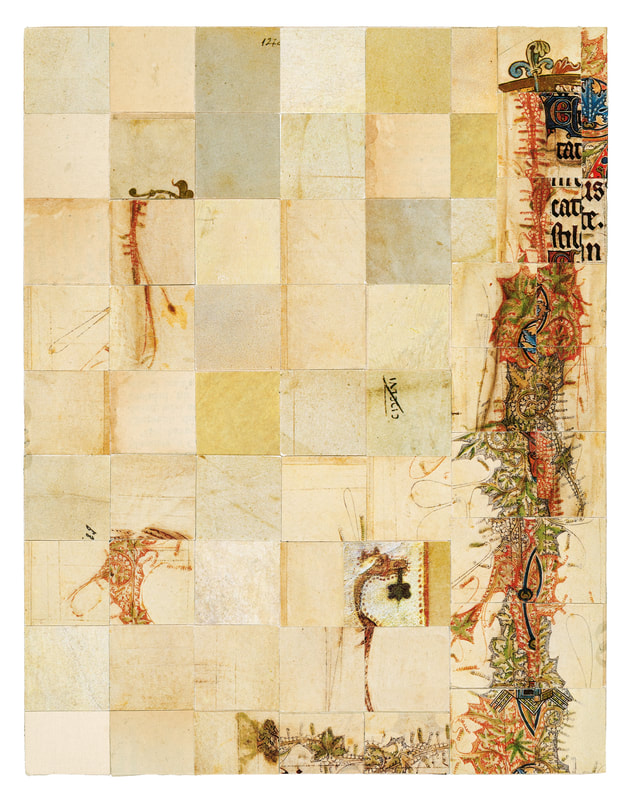

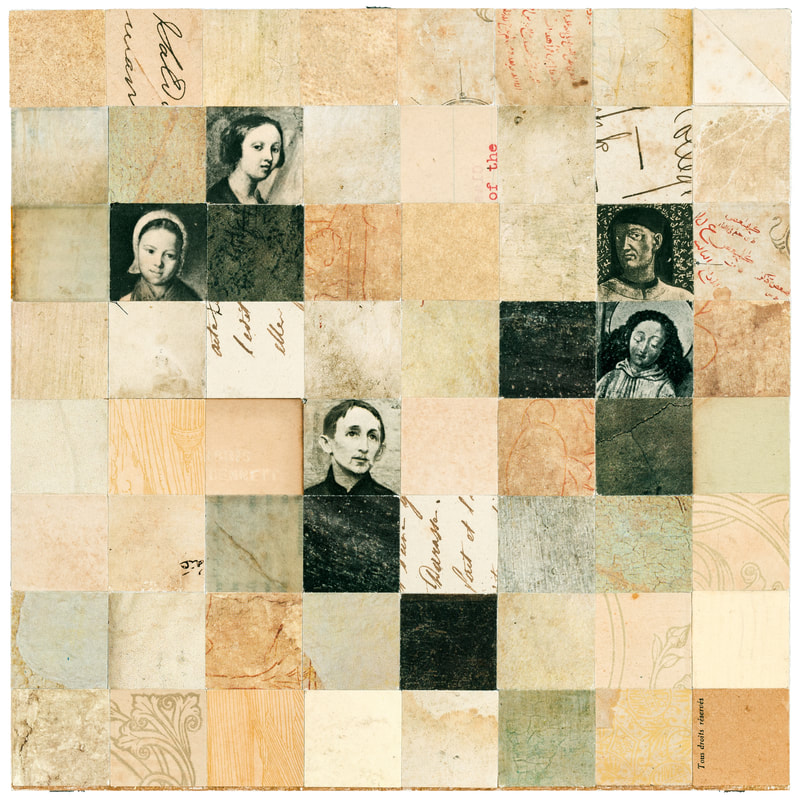

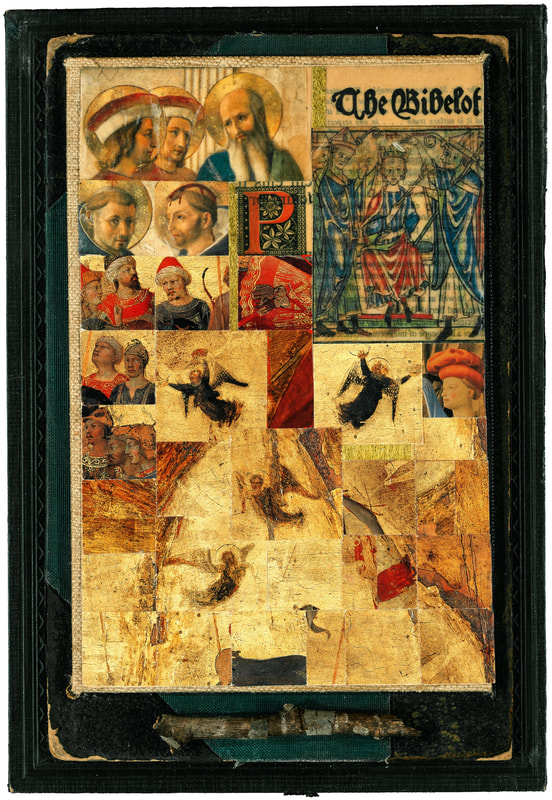

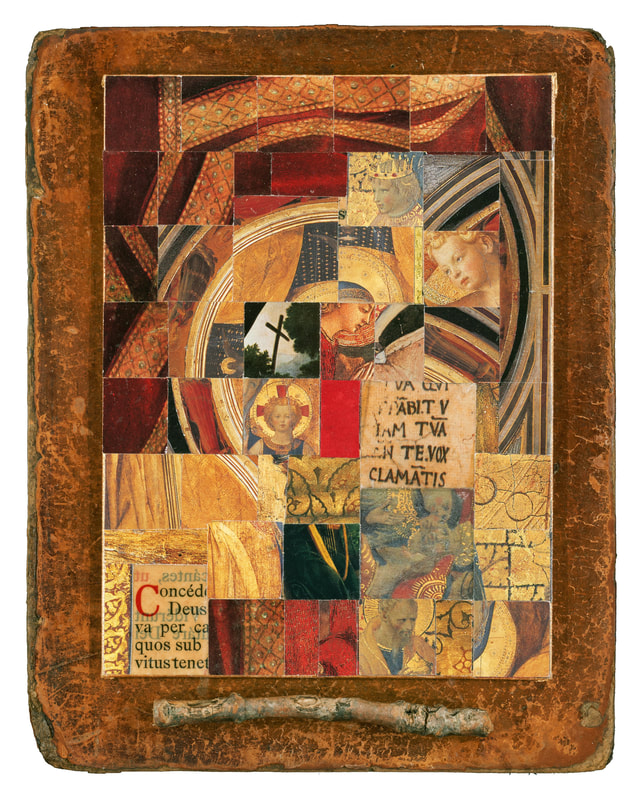

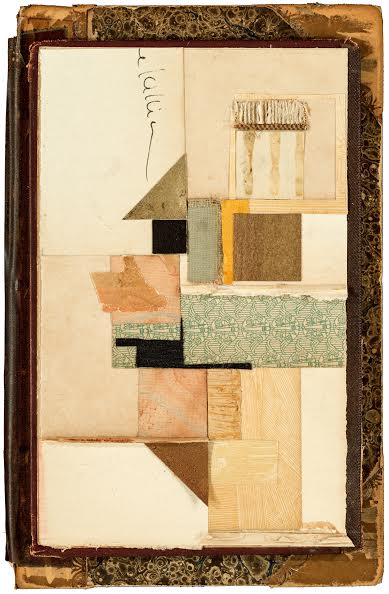

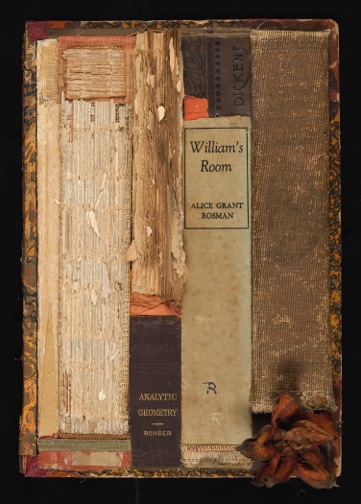

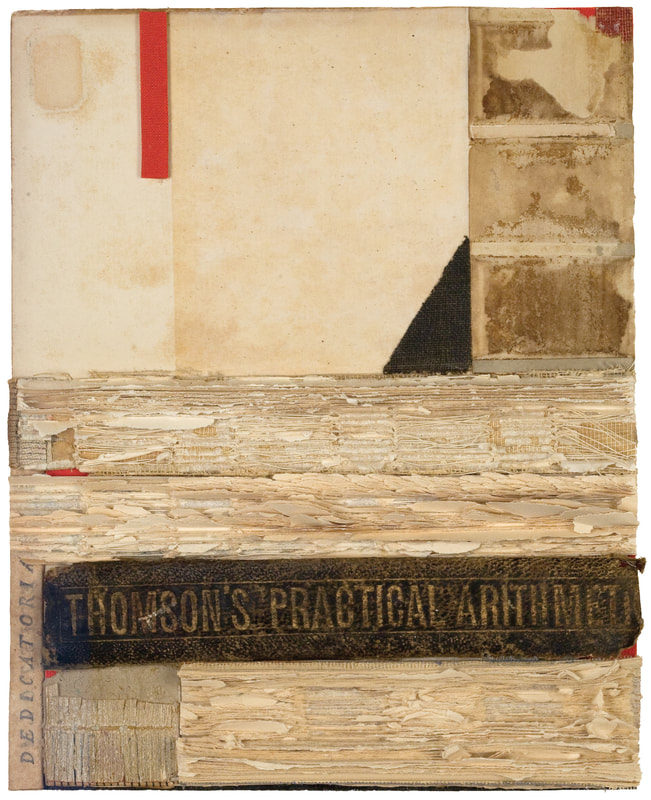

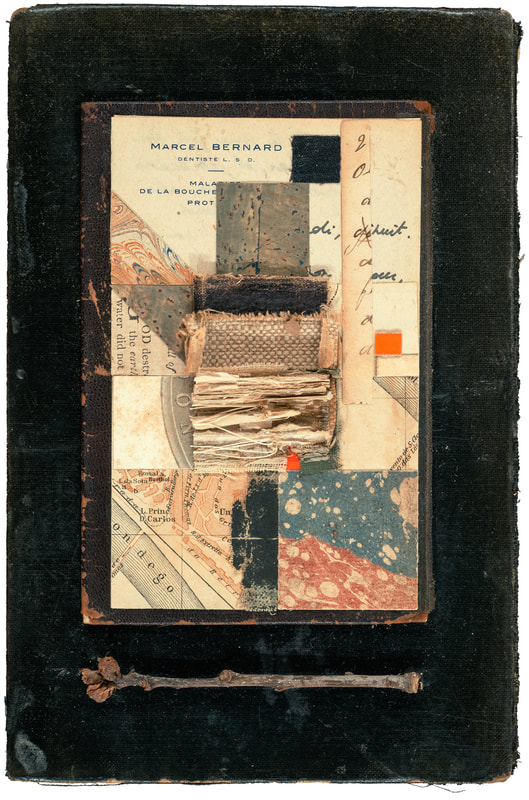

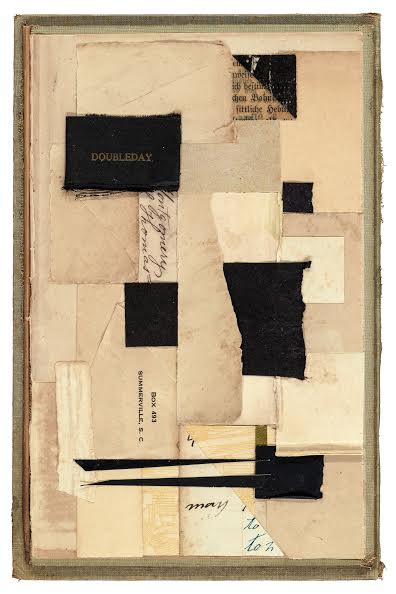

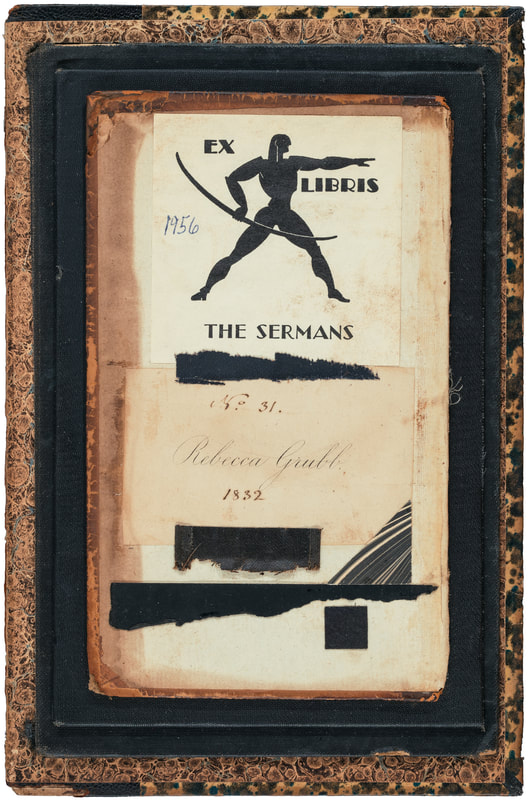

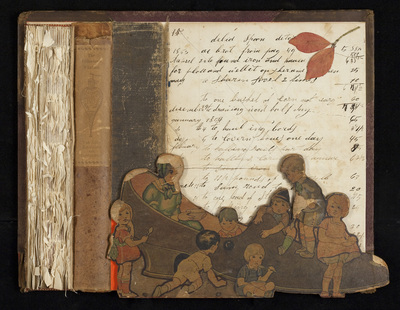

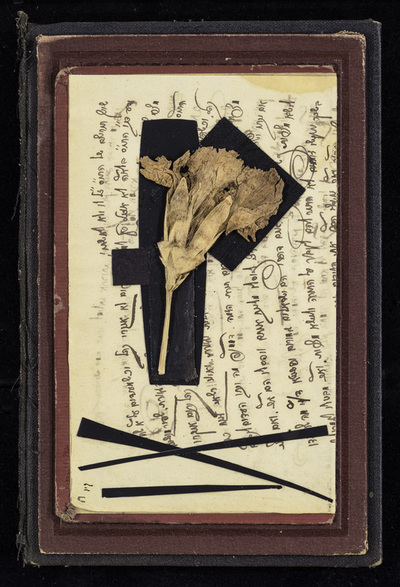

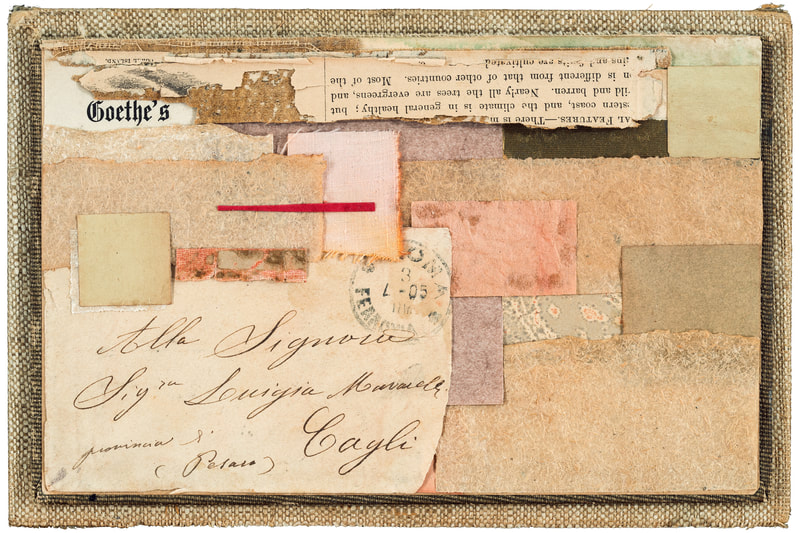

Gutenberg Elegies

Information is a tool but love of reading is a way of life. Like any love, it has a physical dimension. There is more to it than simply ingesting print. It begins with pleasure in the look, feel, and weight of a book. Even the smell of books carries a certain enchantment. Old ones in particular, redolent with history, prod us to imagine a world without us in it, the world our children will inherit. They tilt our attention toward the future by reminding us that the present passes, in Joseph Brodsky’s phrase, “at the speed of a turning page.”

Digital literacy, that darling of techno-utopians, competes now with physical books and the solitary, contemplative print culture nourished by them. Champions of screen reading predict that the paper book—an instrument of modernity—might not be around much longer. Consider, then, the contrasting possibility that in this digital age, books and book arts matter more than ever before.

In our post-Gutenberg world, communication is increasingly disembodied. It flickers across a screen, fugitive and insubstantial. We inhabit an impatient culture, distracted by technologies that advance convenience and facilitate the hunt for information. Techno-readers can carry whole libraries in their pockets. But it is not the gadgetry that ripens thee reader or enriches his life. It is the word itself.

“Read in order to live,” wrote Flaubert, recognizing the umbilical relation between reading and a life well lived. Artifacts gathered from the tangible history of thought, these book collages are meant as metaphors for the fragility of the life of the mind and of cultural memory.

Information is a tool but love of reading is a way of life. Like any love, it has a physical dimension. There is more to it than simply ingesting print. It begins with pleasure in the look, feel, and weight of a book. Even the smell of books carries a certain enchantment. Old ones in particular, redolent with history, prod us to imagine a world without us in it, the world our children will inherit. They tilt our attention toward the future by reminding us that the present passes, in Joseph Brodsky’s phrase, “at the speed of a turning page.”

Digital literacy, that darling of techno-utopians, competes now with physical books and the solitary, contemplative print culture nourished by them. Champions of screen reading predict that the paper book—an instrument of modernity—might not be around much longer. Consider, then, the contrasting possibility that in this digital age, books and book arts matter more than ever before.

In our post-Gutenberg world, communication is increasingly disembodied. It flickers across a screen, fugitive and insubstantial. We inhabit an impatient culture, distracted by technologies that advance convenience and facilitate the hunt for information. Techno-readers can carry whole libraries in their pockets. But it is not the gadgetry that ripens thee reader or enriches his life. It is the word itself.

“Read in order to live,” wrote Flaubert, recognizing the umbilical relation between reading and a life well lived. Artifacts gathered from the tangible history of thought, these book collages are meant as metaphors for the fragility of the life of the mind and of cultural memory.