KATHY HALPER

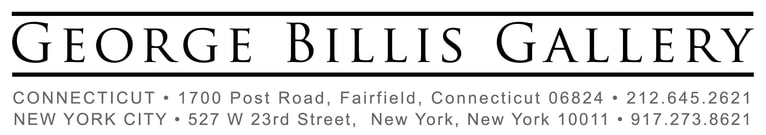

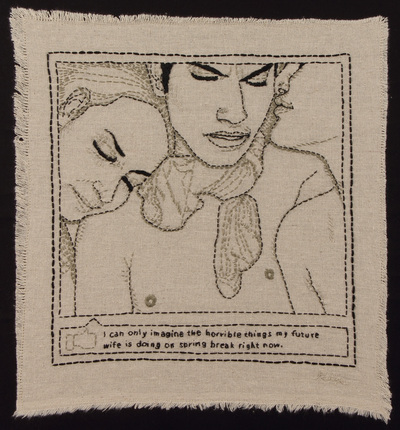

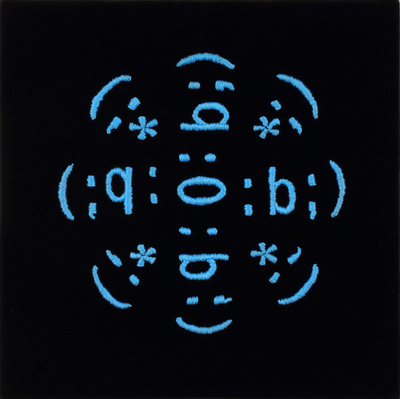

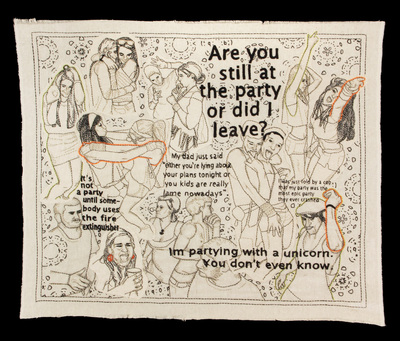

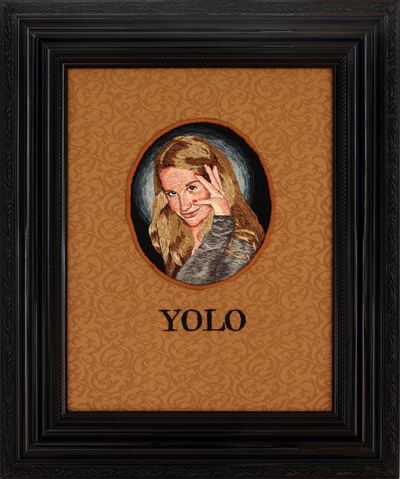

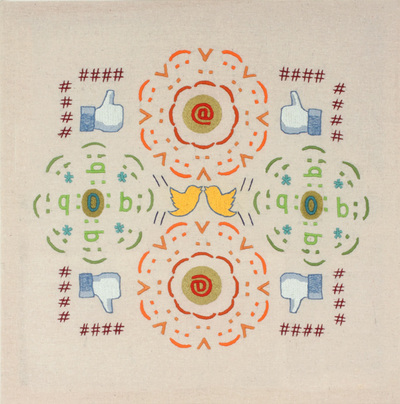

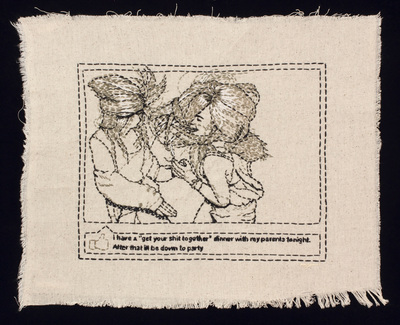

Kathy Halper’s work mirrors adults’ ongoing fascination with youth culture, imbuing it with today’s hyper-social-networked edge. Media theorist Marshall McLuhan predicted the advent of the Internet, suggesting the future of living in a global village that acts and reacts to the pulse of culture. He notes that it is not adults, but rather youth that instinctively and intuitively understand this type of “electronic drama.” This is where Halper’s work begins. Creating embroidered drawings from photographs of adolescents that she finds on social networking sites, Halper’s work questions the disappearing space between public and private online, the subversive use of fabric, needle and thread, and the role that technology plays in shaping adolescence. Her work questions the ways we look and observe, and how adults connect with the youth of today. These questions stem from both her personal experience as a parent, a love of the homemade craft, and an awkward relationship with the Internet.

The artist’s decision to use embroidery rather than painting is paramount. For her, reclaiming this supposed “women’s work” is a radical act, resulting in an empowering, labor-intensive product made by a woman who is also a mother. Much in line with women who have embroidered before her—from the Victorian era onward until today—Halper’s decision to use embroidery rather than painting or photography, provides commentary on the role of women in society today. Her work continues the dialogue around the ever-evolving construction of femininity that “contains its own curious power,” as Rozsika Parker writes in The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine. “The stereotype of embroidery as a vain and frivolous occupation, like the stereotype of the silent, seductive needlewoman, controls and undermines the power and pleasure women have found in embroidery, representing it to us negatively.” Additionally, embroidery is a practice specifically attached to mothers and daughters—and as Halper’s daughter appears on occasion in her social media-inspired embroideries, the familial connection is strengthened or, as it were, sewn into the fabric as skin tones, memory, relationships, and perhaps drops of blood that bleed onto the fabric as she furiously sews.

- Except from Essay by Alicia Eler

The artist’s decision to use embroidery rather than painting is paramount. For her, reclaiming this supposed “women’s work” is a radical act, resulting in an empowering, labor-intensive product made by a woman who is also a mother. Much in line with women who have embroidered before her—from the Victorian era onward until today—Halper’s decision to use embroidery rather than painting or photography, provides commentary on the role of women in society today. Her work continues the dialogue around the ever-evolving construction of femininity that “contains its own curious power,” as Rozsika Parker writes in The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine. “The stereotype of embroidery as a vain and frivolous occupation, like the stereotype of the silent, seductive needlewoman, controls and undermines the power and pleasure women have found in embroidery, representing it to us negatively.” Additionally, embroidery is a practice specifically attached to mothers and daughters—and as Halper’s daughter appears on occasion in her social media-inspired embroideries, the familial connection is strengthened or, as it were, sewn into the fabric as skin tones, memory, relationships, and perhaps drops of blood that bleed onto the fabric as she furiously sews.

- Except from Essay by Alicia Eler